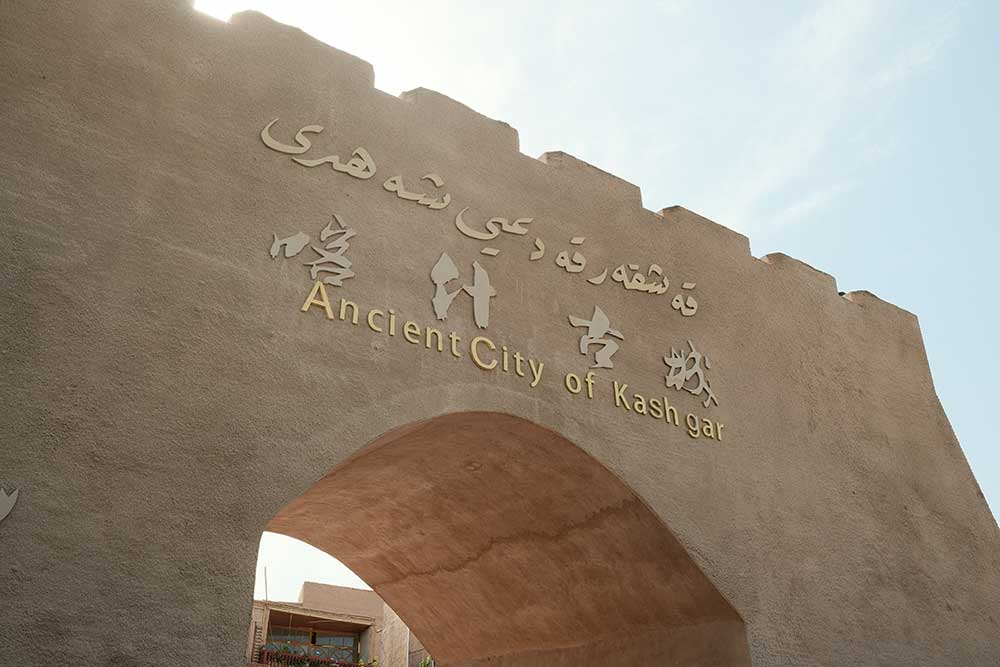

Kashgar is a city with a history of over 2,000 years. (People’s Daily Online/ Zhang Ruohan)

Editor’s note:

The ancient wall of Kashgar, shimmering under the sunset, has been witness to the changes that have taken place in the city over the last two millennia. Over 700 years ago, when Marco Polo first visited Kashgar, a city surrounded by fertile lands and filled with foreign merchants, he was spellbound by its vibrant aboriginal culture. In his well-known book The Travels of Marco Polo, the Venetian adventurer described the city as an international cultural hub, praising its “fine orchards and vineyards.”

Centuries later, under the towering amber walls of Kashgar, merchants standing in front of stalls call out to passers-by to inspect their apricot-colored traditional wood carvings, and Uyghur maidens dance to the rhythm of ancient songs, their orange dresses shining under the sunlight. Time seems to stop in this old city, its traditional culture well-preserved in the amber of history.

As harmonious as it seems to be, traditional culture in Xinjiang, like in many places around the globe, is fading from the modern world. Can the old customs thrive in modern times? Does the young generation still have enthusiasm for traditional culture? How can they prolong the life-span of aboriginal culture? Here in Xinjiang, the people may offer you some insightful ideas.

Memtimin Ghopur’s ancestral house in Hotan is 200 years old. (People’s Daily Online/ Kou Jie)

The first flush of dawn has fallen over Memtimin Ghopur’s 200-year-old ancestral house, and with the gilded coral light comes the enchanted glamour that belongs to a distinguished family that has been practicing traditional Uyghur medicine for eight generations. On the first floor of this ancient mansion, a dimly-lit clinic is filled with all kinds of exotic flora and rare herbs, painting a vivid picture of the daily life of 68-year-old Memtimin.

Living in Tuancheng, a famous neighborhood that features traditional Uyghur-style residences in Hotan, Memtimin’s three-floor home is truly a sight to behold. The mansion’s orange and golden brick walls are decorated with ebony windows with floral carvings and a rainbow-colored windmill, while the small clinic, where incense and herbs send off a hypnotic fragrance, is the best representation of traditional Uyghur culture.

Every morning at 6 o’clock, Memtimin opens his clinic and waits for patients to come. He still remembers that when he was little, the clinic was always crowded with patients visiting his grandfather, the best Uyghur doctor in the neighborhood. His business today is nothing compared to what it once was. Over the entire morning, only two curious tourists came by his clinic, leaving Memtimin quite deflated.

“As a practitioner of traditional Uyghur medicine for my whole life, I have to admit that traditional medicine is losing its appeal to the public. More and more patients now turn to modern medicine and advanced technologies, and our tradition is facing grave danger,” said Memtimin.

After being passed down through eight generations, traditional Uyghur medicine seems to be losing its significance in Memtimin’s family. Of his three children, only the eldest son took up Memtimin’s mantle and became an Uyghur doctor. Memtimin fears that his descendants may eventually give up practicing traditional Uyghur medicine, which he believes also carries Uyghur culture and his family history.

"As long as there are patients who need my help, I will make every effort to help them. But the thought of losing our traditional culture has been haunting me constantly. Can our culture survive in the future? Do our kids still cherish traditional culture?" Memtimin asked ponderously, rubbing his hands together with an anxious air.

Dilnur is a social media influencer who promotes traditional Uyghur artworks. (People’s Daily Online/ Kou Jie)

Equation of tradition and innovation

Memtimin’s concern is shared by 29-year-old Dilnur Iskender, who realized that although they bring convenience to her life, modern technologies have also threatened the existence of old Uyghur customs, erasing her childhood memories and the traditional way of living.

“In 2017, a wooden spoon that I had been using since I was a kid was broken. It is made by traditional Uyghur wood carving techniques, and I was shocked to learn that it was impossible to find a replacement, because no one was making those things anymore,” said Dilnur.

After going off in search of her childhood memories, Dilnur came to Hotan, where traditional Uyghur culture is well preserved, to find the last Uyghur wood carving masters. After several months of searching, she could find only 10 craftsmen who knew these traditional techniques, and the youngest of them was over 40 years old.

"All of them had stopped making wood carvings when I found them, because they could not make money from it, while the young generation is reluctant to learn these traditional techniques," said Dilnur.

"Technological advances have threatened the existence of our traditional culture and art, but we can also use modern technologies to revive them. With this in mind, I decided to livestream and sell traditional Uyghur tableware online," added Dilnur, who resigned from her job as a substitute teacher and became a full-time social media influencer in 2020.

After sharing emotional stories of her childhood memories online, Dilnur began to attract more and more attention. Clients from across China were touched by her stories and the interesting cultural significance behind the wooden tableware. They began ordering all kinds of Uyghur wood carving artworks from her, and even fans from other nations such as Russia and Kazakhstan have contacted her, hoping to get an Uyghur spoon for themselves.

"Every day, I can sell around 20,000 yuan in wooden tableware. I have signed contracts with all the carving masters, and now they are happy to continue their work. I feel really happy about that," said Dilnur.

“Traditional culture has a unique appeal to the public. As long as we can tell good stories of our culture to the outside world, our tradition can survive and even thrive in modern times,” added Dilnur.

Gulbanum’s innovations have breathed new life into the once-neglected traditional Uyghur dance. (People’s Daily Online/ Kou Jie)

The enthusiasm for injecting modern vitality into traditional culture is shared by many young people in Xinjiang. 30-year-old Gulbanum Imin, a teacher and an owner of a local Uyghur dance school, is a local celebrity in Korla. Her school, which teaches traditional Uyghur dance, has attracted over 400 students from between the ages of 5 and 60, most of whom are not Uyghurs.

“Though traditional Uyghur dance is loved by many people, it is still necessary to add modern elements to it. As a dance professional, I’ve absorbed ideas from all kinds of dances, including ballet and jazz, and I’ve adapted and added these new elements into traditional Uyghur dance,” said Gulbanum.

Gulbanum’s innovation has breathed new life into the once-neglected traditional Uyghur dance. She has been invited to many cities to perform her new dances, and to tell stories of traditional Uyghur culture on television.

“Tradition is the source of inspiration for innovation, while innovation can prolong a tradition’s life span, bringing new life to old culture. There is an equation of tradition and innovation. As long as you find the balance, you find the secret to keeping tradition alive and allowing it to thrive,” said Gulbanum.

Ibrahim’s biggest wish is to play dombra and sing Uyghur songs outside Xinjiang one day, and to see the ocean. (People’s Daily Online/ Kou Jie)

“When one loves one’s art, no service seems too hard.” 11-year-old Ibrahim MemetEli may know nothing about the American writer O. Henry, but his love for dombra, a traditional musical stringed instrument, has shown the truth behind this famous statement. Here in Awat Central Primary School, Ibrahim and his friends have been learning dombra for years, practicing traditional music everyday.

“I spend many hours a day polishing my skills in singing and playing dombra, but I feel quite happy about it. It makes me feel like I am very special, and I have something that others don’t,” said Ibrahim.

Ibrahim is not the only student who is enthusiastic about traditional culture and has access to it. At his school, which has 2,722 Uyghur students, the kids have a choice of several Uyghur cultural courses, including dancing and paper carving.

"Most students in our school are from remote villages. Though they have a love for traditional art, they have few resources to learn it. Here in our school, all the courses and equipment are free to students. As long as they have an interest, they are welcomed," said Zhao Yuguang, a teacher at the school.

In addition to traditional music, Ibrahim’s other hobby is studying languages. According to local regulations, most courses at Uyghur schools are taught in both Uyghur and Mandarin, while students are also required to study English as their foreign language.

“I am not very good at speaking Mandarin and English, but I think I should study harder to master them. It is my dream to play dombra in big cities outside Xinjiang. If I can’t speak those languages fluently, how can people understand the beauty of my music?” said Ibrahim.

“The Uyghur language is the children’s cultural root, Mandarin represents their identity as Chinese, while English makes them international citizens. By learning three languages, our children have triple identities,” said Zhao, adding that multilingualism and multiculturalism have made his students more culturally tolerant and open-minded.

“I have never been anywhere outside Xinjiang. It is my dream to see the vast ocean, and I really hope I can bring my dombra with me, making friends with people around the world, learning their culture and introducing mine to them. It would be so cool,” said Ibrahim.