Shiliuyun-Xinjiang Daily (Reporters Li Yang, Yin Lu, Ren Jiang) news:

“Muqam, is the morning breeze of dawn,

And a prelude to the rhythm of the world.

Even the larks are humbled by her.

One can hardly comment on that treasure.”

When he first heard this melody, Wan Tongshu was 28 years old. Even though he didn’t understand the lyrics written in the language of the Uygur ethnic group, it was as if he had touched a whole new world of art, a world so beautiful and magical that he was drawn to it.

Since then, he had traveled around the north and south of the Tianshan Mountains, crossing deserts, grasslands and the snowy mountains, in winter and summer, for only one thing - to save Muqam.

And so, his journey lasted for more than 70 years.

Once, Mukam was on the brink of being lost, just like the barren desert he walked through in his early years.

Now, the Xinjiang Uygur Muqam Arts of China is known worldwide, just like the large ocean he faced in his old age.

This cultural treasure survived and became a legend. The musicologist Wan Tongshu spent his life guarding it and also made his life legendary.

At his home in Xiamen, Wan Tongshu has displayed the book of Twelve Muqams at a prominent place in the living room. (Photo provided by Wan Tongshu’s family)

I

In 1923, Wan Tongshu was born in the British Concession in Hankou, Hubei Province. He spent his teenage years in the chaos of warlords and the Japanese invasion and had been passionate about music since childhood.

In the early spring of 1938, Japanese airplanes attacked three towns of Wuhan. At the Hankow Customs House, the famous musician Xian Xinghai led 10,000 people to sing “defend Wuhan with our invincible power”. Hearing this, 15-year-old Wan Tongshu stood in the crowd, clenched his fist, and his blood rushed. Thus, he set his mind on serving his country with music.

After the founding of the People’s Republic of China in 1949, Wan Tongshu became a young talent at the Central Conservatory of Music. As a talented singer and composer, and a master of many musical instruments, he became a rising star. His wife, Lian Xiaomei, is also a talented musician. However, just when people expected them to reach the prime time of their artistic careers, their work and lives suddenly changed.

In March 1951, Lv Ji, the president of the Chinese Musicians’ Association, told Wan Tongshu, “we are going to assign you to work in Xinjiang where a set of music called the Twelve Muqams is about to disappear and must be saved immediately.”

The Twelve Muqams? What is that? Wan Tongshu was dazed.

Hearing her husband’s words, Lian Xiaomei was even more puzzled. Her first question was, ‘where is Xinjiang?’.

In March 1951, before leaving for Xinjiang from Beijing, Wan Tongshu took a family photo. (File photo)

Ⅱ

It was also in March 1951, in the southwest of the Taklimakan Desert in Xinjiang, sand covered the windy sky, and the bud of the badam (almonds) tree was trembling on the branches.

A 70-year-old man hobbled along at the end of the old street of Wusitangboyi in the ancient city of Kashgar. His shadow lengthens in the setting sun. He sang as he walked with his slightly husky voice, which had been polished by the wind of the desert for many years:

“I run around the desert with all my might,

For what I pursue, I must fight.”

His name was Turdi Ahon, and what he sang was the Twelve Muqams

The unique and comprehensive Xinjiang Uygur Muqam Arts of China, which integrates songs, dances and music, was formed in the middle of the 16th century and has evolved for more than 400 years, reflecting all aspects of the history and social life of the Uygur ethnic groups of China’s Xinjiang with rich musical forms. While absorbing a large number of elements of traditional Chinese music, the Muqam has also greatly enriched it. It includes the Twelve Muqams, Dolan Muqams, Turpan Muqams and Hami Muqams. Among them, the Twelve Muqams is the most representative for being the largest and most complete in structure.

However, back in the old society, the Muqam artists were regarded as inferior, bullied by the local landlords and magnates, wandering around, and living precarious life. Due to the hardship of life, the number of old artists decreased. Thus, in the end, only Turdi Ahon was left to sing the entire Twelve Muqams, and even his son could not do that.

Saifudin Aziz, vice chairman of China’s Xinjiang back then, was shocked to know this situation by chance and reported it to Premier Zhou Enlai in person when he arrived in Beijing. Premier Zhou immediately said that the CPC Central Committee would support it and that such a treasure must be saved!

III

It is necessary to send all-around music talents to save this artistic treasure. According to the requirements of the former Ministry of Culture and the National Ethnic Affairs Commission, the Central Conservatory of Music finally placed the heavy task on Wan Tongshu after several terms of selection.

Holding their one-year-old daughter Wan Shixun, Wan Tongshu and his wife embarked on a train from Beijing to Xinjiang. Like countless young generations of that era, they were apprehensive and excited, inspired by the pride of the founding of the People’s Republic of China and full of dreams for the future.

First by train, then by car, and then by plane, the couple traveled several times to reach Dihua (present-day Urumqi). The National Ethnic Affairs Commission specially arranged a military plane to pick them up as the couple heard that there were still bandits on the way to Xinjiang after arriving in Lanzhou.They were picked up at the airport by a horse-drawn carriage known locally as the “six sticks”. With the horses trotting and the bells jingling, the Wan Tongshu family entered the city gate in the spring breeze.

Suddenly, the Uygur coachman started to sing. It was a tune that Wan Tongshu had never heard before, and although the lyrics were beyond his understanding, the bright rhythm and cheerful mood struck him instantly.

“What’s this song?” He asked. But the coachman wasn’t sure. He only knew that everyone back home could sing a few lines. Wan Tongshu followed and learned to sing, and the carriage moved along briskly in the song.

Settling in, Wan Tongshu began to familiarize himself with the city. There was a lake named Red Lake near the drama troupe where they worked at the time, which was lined with trees, including a hundred-year-old tree with lush branches and leaves that shaded the sky. In his spare time, Wan Tongshu would go there for a walk.

One evening, he went to the lake for a walk again, and before he reached the ancient tree, he heard a sound of a drum, a certain instrument and a song that immediately reminded him of the coachman’s singing. Wan Tongshu stopped to listen carefully and soon became engrossed. As one sound was over, another was started, apparently by another singer with a different tune and accompaniment. Several singers were under the hundred-year-old tree, but Wan Tongshu did not come closer. Instead, he stood far away to listen and could not bear to disturb them.

The next evening, Wan Tongshu had an early dinner and went closer to the ancient tree, quietly listening to the sound all night. From that tune, he heard joys, sorrows and peace of mind, and felt the melancholy, happiness and all the tastes of life reflected by it.

On the third day, Wan Tongshu couldn’t help but find out who the singers under the tree were. After asking, he found out that they were folk artists who were invited from all over Xinjiang to record the Twelve Muqams, and what they were singing was Muqam, the “origin of all songs” of the Xinjiang Uygur ethnic groups.

One of them was an old man of medium height with a long beard and thick eyebrows, wearing a Badam flower hat and a purple and green striped coat. The Taklimakan sun bronzed his face, his wrinkles stretched like the canyon in the Tianshan Mountains, and his dark brown eyes shone brightly. Here he was, the famous Turdi Ahon.

That was how a young musicologist from Beijing and a renowned folk artist from Xinjiang met. The language barrier was not an obstacle, as music was their common language. Turdi Ahon sang the Twelve Muqams to Wan Tongshu, who played the violin for him. Together, they soon became friends.

Turdi Ahon is the fifth generation of his musical family in the hometown of the Twelve Muqams. He learned to play musical instruments at six, understood the Twelve Muqams at 12, and could sing them without difficulty at 20. Hundreds of songs and thousands of verses from the Twelve Muqams were all in his blood.

What to do when the recording could not begin immediately, as there wasn’t a recording device in Xinjiang?

Desperate for help, Wan Tongshu turned to his superiors in Beijing. Thus, a nationwide search was launched, which ended with the purchase of a wire recorder from Shanghai, said to be the disposal material left behind by the American army when they evacuated mainland China.

A working group for the collation of the Twelve Muqams was formally set up with Wan Tongshu as its leader, musician Liu Chi and his brother Liu Feng, composer Ding Xin and poet Krim Hojia as members.

Wan Tongshu (second from left, front row), Turdi Ahon (second from right, front row), and other members of the Twelve Muqams working group in the 1950s. (File photo)

Get everything ready to record! However, there was a problem with the electricity. At the time, the electrical voltage was unstable in Dihua, so the sound fluctuated largely. Fortunately, the radio station was able to help by getting a hand-cranked generator and offering the studio to the team. Despite the limited conditions at the time, the local organization and authorities managed to solve all their difficulties.

On August 10, 1951, Turdi Ahon took his Sattar, went to the studio, and sat down to begin the audition to set the basic tune for the songs. His son, Uxur Turdi, sat next to him to play the drum.

Here began the first recording.

IV

“I fell deeply into Muqam,

Which lingers around in my heart.

If I’m addicted to the longing for love,

I shall play it to my beloved.”

Turdi Ahon loosened his voice. His songs were full of salutes to nature, revelries and shouts from the field, ghostly whimpers, and the sorrows and ecstasies of love.

The old man closed his eyes tightly, waving his arms to play the piano and swaying to the music.

He could not stop while singing, and the operator of the hand-cranked generator could not stop for a second either but kept cranking at an average speed. At the end of a song, the operator was sweating profusely. As the day went on, his arms soured so that he could not move. So the radio station assigned three more operators to take turns controlling the generator during the breaks between songs.

After a long day of recording, Wan Tongshu came to Turdi Ahon and asked, “Why do you always keep your eyes closed when you sing?”

The old man replied that he had been a wanderer and had grown up seeing the cold eyes of the rich who paid them. So he would never dare to look directly at their face.

Hearing this, everyone was silent.

After a long time, Wan Tongshu said, “It’s the People’s Republic of China now, and people are the master of the country. Please let go of your voice and let the show start!"

The old man was curious and excited to hear his own voice coming out of the recorder for the first time. He caressed the wire recorder with his fingers smoothed by strings over the years, and his deep eyes were filled with tears.

It took nearly 20 hours to sing the entire Twelve Muqams. The recording lasted for over two months and ended in late October, with the result of 24 wire tapes. It was the first time the Twelve Muqams were recorded systematically after the founding of the People’s Republic of China.

Accompanied by the melody of Muqam, Wan Tongshu and Lian Xiaomei’s second child, a lovely boy, was born. This double gift brought the couple great happiness.

V

Sound recording was just the beginning, but there was more difficult work ahead: notation.

As a learner of Western music, Wan Tongshu was familiar with the twelve-tone-equal temperament, which differs from the musical system of Muqam. In particular, Muqam is rich and complex in rhythm, tune, beat, and melody. It is difficult to note it in a pentatonic form, so many musical notes cannot be marked.

To solve this problem, Wan Tongshu reviewed a large number of music references at home and abroad, pioneered the compilation of notes, including smooth glides and chants, and created a set of two horizontal lines to note the pitch of drums. Later, these innovations were widely recognized and used.

He would often have to play the recording dozens of times only to understand a single line of the song. The recording medium of the wire recorder is a hair-thin wire, which was easily broken on repeated playbacks, resulting in a mess that can take up to a week to sort out. Any other person would soon be distracted, but Wan Tongshu treated it with patience and calmness, cleaning it up, straightening it, winding it up, then picking it over again to listen.

At that time, electricity was only available for five hours a day in Dihua, and the power went out at 3 am, so Wan Tongshu and Lian Xiaomei fought to take notes every night.

Wan Tongshu, sitting near the recorder, listened intently and took notes quickly, while Lian Xiaomei was controlling a transformer to adjust the voltage. Not even for a moment did the two of them dare to relax.

Their newborn child was three months old when he was diagnosed with acute pneumonia. The doctor said he had to receive medical treatment, but the Wan Tongshu couple could neither leave their notation work behind nor leave one in the hospital to look after the child, as the other could not do the notation alone. They begged and pleaded with the doctor to prescribe medicine for their child to take home.

One night, after feeding the child, the couple concentrated on their notation. When the power went out at dawn, they found the child had stopped coughing, and then they exhaustedly headed to sleep.

Early the next day, heart-rending cries suddenly spread from this home.

That fleshy little boy never woke up again.

Wan Tongshu waved his hammer and nailed a small wooden box. He wiped his tears, carefully put his child into the box, and buried him on a hill.

That evening, as soon as the electricity was available, the couple sat down again in front of their machines respectively and continued note-taking.

As a result of using his left chest against the table for a long time, Wan Tongshu’s left chest was deformed and his eyes were highly nearsighted. The buttons on his recorder were shining as Wan Tongshu rubbed them too much. His left fingers wore thick calluses, and eventually, he could not bend his left hand and lift his left arm. Lian Xiaomei persuaded him to see the doctor, but he disagreed and scolded his wife for holding him back. Lian Xiaomei wiped her tears silently in anguish, went to the hospital to get a prescription for him, and rubbed the medicine on Wan Tongshu’s arm and fingers. Even so, she still transcribed most of Wan Tongshu’s notes.

It took nearly five years for the Wan Tongshu couple to complete this tedious and arduous task.

In 1954, tape recorders became available on the market. To preserve a complete set of the Twelve Muqams with better acoustics, Wan Tongshu invited Turdi Ahon to record again. On the other hand, the working group invited a number of translators, Uygur poets and musicians to participate in the translation and interpretation, and translated the lyrics written in Chahetai language word by word into the modern language of the Uygur ethnic groups. The Twelve Muqams, sung by Turdi Ahon, were finally validated, which included 340 music tracks with 2990 lines in lyrics.

In August 1956, Wan Tongshu brought this result to Beijing, which attracted immediate attention. His superiors considered it a big event in the history of Chinese music and decided to publish the musical notes and recordings of the Twelve Muqams.

Wan Tongshu was so excited that he wanted to tell Turdi Ahon the great news as soon as he returned to Xinjiang. However, he was told that the old man had already passed away.

VI

Once, when Wan Tongshu was passing through Turdi Ahon’s hometown on his way to southern Xinjiang, he made a special trip to visit his tomb.

The old artist who praised love with Muqam and always asked, “do I need to sing it again” when he recorded, seemed to be standing in front of him, and Wan Tongshu could not help but burst into tears.

Some folks nearby came to find out and wondered: who is this emaciated man with glasses?

Knowing his identity, someone shouted out, “you are Wan Tongshu! Master Turdi has extolled you in his songs, saying that you are the soul of the Twelve Muqams!”

It turned out that after returning to his hometown, Turdi Ahon often missed Wan Tongshu and wrote a song called “The Soul of Music”, which he sang with the tune of the Twelve Muqams:

“I miss a man at times

Who saved the Twelve Muqams.

His recordings and notes remain alive,

So that my Muqam will never die.

His devotion and sacrifice

Helped Muqam reach the world.

He is the living soul of the Twelve Muqams.

His name is Wan Tongshu.”

In 1960, they released two volumes of notes for the Twelve Muqams, which were exhibited at the entrance to the third conference of the China Federation of Literary and Art Circles at the end of July that year, attracting the admiration of delegates from all over the country.

Later, the major media in China reported this significant literary achievement, and the foreign newspapers also gave a full-page display, making it a sensation.

At that time, traditional Uygur instruments and performances were passed down from artist to artist, lacking theoretical conclusions, so they could not be easily grasped by beginners. Wan Tongshu was then reminded by Lian Xiaomei to compile a book on Uygur musical instruments, by using his sketches and notes he had taken over the years. Since then the origins, evolution and performing methods of 17 traditional Uygur instruments have been systematically explained and introduced, representing another pioneering work in the studies of the history of Chinese instrumental music.

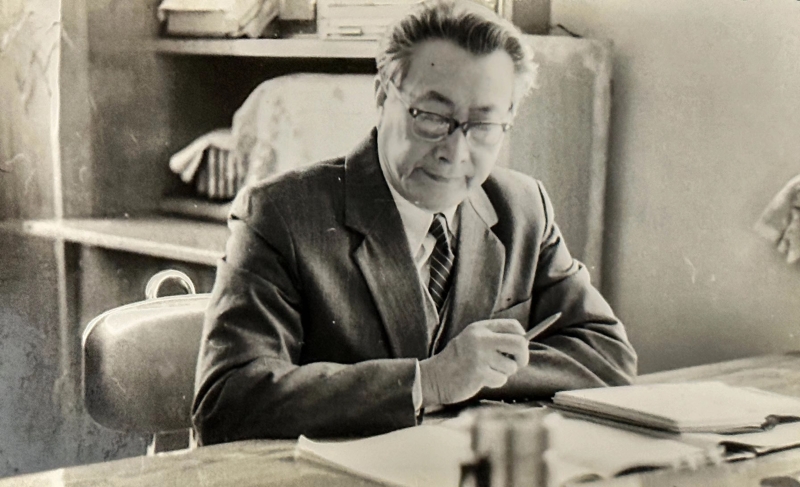

Wan Tongshu at work. (File photo)

VII

In Xinjiang, the melody of Muqam echoed everywhere, in streets and alleys, teahouses and restaurants, villages, towns, and even from donkey carts, camel caravans, and bonfires. In the joyful sounds of Muqam, babies are born, the young are married, and the old who have walked through the hardship of life return to the ground. Muqam has witnessed people’s joys and sorrows throughout their lives.

The folk artists who make their living by singing Muqam are known to the people as “muqamqi”. Wherever they go, they bring this artistic charm with them.

Starting in August 1957, Wan Tongshu took a few people from the research team and traveled along the northern edge of the Kunlun Mountains in an open truck to various parts of southern Xinjiang in search of more muqamqi. At that time, the roads were all dirt, and the trucks were so bumpy that they could not even stand up after a day of driving. Wan Tongshu’s soles wore out walking on the dusty country roads, and his toes bled, but he kept going like a camel.

Wan Tongshu (second from left) and his colleagues were collating the Twelve Muqams in southern Xinjiang in the 1950s. (File photo)

In Moyu County, there is an 80-year-old artist called Patar Harf, who can sing nine sets of Dolan Muqams. But the old man turned Wan Tongshu away when Wan visited him several times. It turned out that Patar had been bullied by a man from the village who asked him to perform Muqam at a feast. The old man sang for three days until his voice was hoarse, but the bully told him that he wouldn’t pay for his failed singing. The stubborn old artiste refused to sing again.

It was through a donkey that they unraveled the knot. One day, Patar rode his beloved donkey to the market, but someone stole his donkey, so he stood at the crossroads and sang Muqam aloud to release his anger. Wan Tongshu retrieved the donkey with the working team and local staff. The old artist was so excited that he burst into tears when he received the reins from Wan Tongshu’s hands. Thus, a complete set of Dolan Muqams got recorded for the first time.

In 1982, Wan Tongshu saved the Hami Muqams.

Ahonbek Subur, an old artist who sang a whole set of the Hami Muqams, used to know Wan Tongshu. When they reunited years later, the old artist was already in his eighties, and his teeth were almost gone. Wan Tongshu took him to the hospital and had his teeth set. Thus, Ahonbek was confident and excited, and his desire to sing rose like a fire. Within ten days, the old man had recorded a whole set of Hami Muqams.

The Yiwu Muqam is a typical representative of the Hami Muqams, inheriting traditional singing and performance forms with a unique style. However, one of the main inheritors of the Yiwu Muqam, the old artist Jilil Adil, lived secluded in the mountains, changed his name, and stopped singing for over 20 years.

After the reform and opening up, Wan Tongshu consulted many people, crossed many mountains, and after several twists, finally found him and presented him with a brand new Sattar. Jilil hugged Wan Tongshu firmly. Only then did the neighbors realize that a muqam master was living near them.

The next day, the villagers from far and near set up the stage to see him perform.

With great spirit, the old artist sang:

“My drowsy Muqam awakened anew.

I shall sing it again with you.

Let it be heard in all corners of the world.”

VIII

For most of the few photographs left of Wan Tongshu, he is described as sitting cross-legged anywhere available while recording Muqam, with his hair stubbornly standing up, his lips chapped, and the cloth shoes on his feet soaked with dirt that one can hardly distinguish their original color.

When thirsty, he would open the bottle of water carried with him and take a sip. If he couldn’t find water, he would drink from the puddles on the side of the road. When there was no place to stay, he would sleep in a car, sometimes in a pile of grass, and even in a graveyard. He traveled around the countryside tirelessly to wherever there were old artists.

He was chronically malnourished and physically exhausted. Once, he had a stomach ache while in southern Xinjiang collating music and vomited blood profusely. To nourish him, the local villagers brought him a stewed lamb liver which they fed him by turns. There was another time when he had a large boil on his back, which caused a high fever, and the medical conditions of the county could only reduce the inflammation and remove the pus to bandage it. Before bringing down fevers, he got on his donkey again to collect songs.

The old artists said that Wan Tongshu was the savior of Muqam and was the “muqamqi” they admired most.

“Dad later said that it wasn’t that Muqam couldn’t leave him, but that he couldn’t leave Muqam.” Wan Tongshu’s youngest daughter Wan Jing recalled.

It is inexplicable that Wan Tongshu, who has dedicated his whole life to music, never talked to his children about music at home.

Inspired by her family, Wan Jing also chose to pursue music as a career, but as far as she can remember that her father never coached her.

When a person puts all his energy into his work, ends up exhausted, and comes home not wanting to mention another word about work, just wishing to take a breath - this may be the case with Wan Tongshu.

Once, a worker wanted to learn to sing and came to Wan Tongshu for guidance, who taught him to use the feel of yawning to make his voice. Wan Jing, standing nearby, heard this and quietly tried it out, and it worked. When she returned to school, her vocal teacher was amazed and complimented her on how much she had improved her voice. Wan Jing said that her father was a musician and that he had taught her a new method, yet she felt a little sad.

Wan Tongshu was not a perfect father. Wan Jing said, “We were somehow unfamiliar with Dad, and he was so strict that we were even a bit afraid of him. We didn’t dare to take things in his study, not even a newspaper.”

Wan Tongshu traveled a lot and rarely disciplined his children. All three of his children had the experience of being placed in their second uncle’s home in Wuhan. Wan Jing was sent there at one year old and was only picked up when she was six and a half. His eldest daughter, Wan Shixun, often went to kindergarten by herself. She, trembling with fear, crossed several blocks with her tiny legs. Once, when it was dark, and her parents had not come to pick her up, the kindergarten teacher had to take her to Wan Tongshu’s office to look for him, only to find the room was bright. It turned out that the couple had been at work and had even forgotten about picking up their daughter.

To Wan Tongshu, saving Muqam is a top priority, and everything else needs to step aside, including his family. However, he is patient with other kids.

In his neighborhood, there was a young Uygur boy named Nusrat Wajidin. The sound of the piano and violin from Wan Tongshu’s house attracted him to music. He also got a violin and played it every day in the alley and on the roof.

Nusrat was good mates with Wan Tongshu’s son, Wan Shijian. “Whenever I went to his house and saw his father’s bookcase full of books about music, I couldn’t take my eyes off of it,” Nusrat recalled.

Once, with the approval of Wan Shijian, Nusrat took a copy of Spossobin’s Harmonics. This incident, which they thought was unnoticeable, was soon discovered by Wan Tongshu.

“Are you the boy who plays the piano in the middle of the night?” Wan Tongshu straightly asked while checking Nusrat up and down and then asking him to come to his house to learn music more often.

In that small study, Nusrat learned to play the trumpet and violin with Wan Tongshu and acquired music theory. Later, the former “roof boy” was admitted to the Tianjin Conservatory of Music and became a famous musician in Xinjiang.

Naturally, Muqam became the most important source of his musical inspiration. Starting from the symphonic suite “Boiling Tianshan” for graduation to the symphony “Muqam Overture” and “Symphonic Suite of the Wuzhalemu Muqams”, and the symphonic poem “Homeland”, Nusrat has been exploring the “symphonicization” of Muqam.

IX

Wan Tongshu (left) discusses Muqam with Turdi Ahon’s youngest son, Kawul Turdi (right), in the late 1980s. (File photo)

In the rhythm of Muqam, Wan Tongshu came to Xinjiang in his prime.

In the afterglow of Muqam, Wan Tongshu stayed in Xinjiang and gradually grew old.

His children went to settle in the eastern part of China, and time and again, they tried to persuade their parents to go with them, but it was difficult for them to leave this vast land and Muqam, which had become one with their lives.

However, Wan Tongshu’s condition deteriorated, and at 75, he and his wife had to move to live with their children.

The day before he was due to leave, he pulled an unwrapped cassette from his drawer and held it in his hand for a long time before picking up the phone and calling his student, Dilxat Parhat, to come over for a moment.

Wan Tongshu admires his student Dilxat who was working at the Xinjiang Art Institute at the time. When Dilxat came to his teacher’s house, he saw Wan Tongshu sitting in the middle of the big and small packages he had already packed. Wan Tongshu handed him the tape, smiled calmly, and said, “These are some characteristic Muqams I have collected. I haven’t figured out which of the Twelve Muqams they belong to, so I’ll leave them for you to figure out.”

Dilxat, who later became the head of the Xinjiang Mukam Art Troupe, recalled that his palms were slightly sweaty once he received the tape, knowing he was taking on a great responsibility.

At that moment, a thousand thoughts came to Dilxat’s mind, but all he could say was, “Don’t worry.”

Soon, an ordinary couple appeared in a neighborhood of Xiamen, Fujian. The neighbors were slightly impressed that the old man often carried a small tape recorder when he walked or picked up the newspaper and listened to songs that no one could understand.

In 2005, the Xinjiang Uygur Muqam Arts of China was approved by UNESCO as a “Masterpiece of the Oral and Intangible Heritage of Humanity.”

The moment he received the news, 82-year-old Wan Tongshu slowly walked into his study, turned on his tape recorder, and listened to his favorite excerpts from the Rak Muqams. Outside the window, the sea is breezing. He gently closed his eyes, nodded to the rhythm, and raised his right hand to the beat smoothly.

On 9 January 2023, Wan Tongshu closed his eyes and never opened them again. The 99-year-old musicologist drew the last note of closure of his life.

His tombstone sits on a slope facing the sea, surrounded by grass and trees, with blue waves rippling in the distance. The sea is also like a never-ending song, roaring and chanting softly at times.

At the same time, in the theatre of the Xinjiang Muqam Art Troupe that is thousands of kilometers away, the musical “Muqam Memories” composed by Nusrat was performed again, nearly to a full house. Audiences from all over the country are once again hearing the enchanting and unique melody of:

“I shall present you with the truth of Muqam.

It praises love,

So one’s passion is lightened up.

It is the fruit of diligence and wisdom,

And the musical poem of ancient and youth, sorrow and delight.”

(A written permission shall be obtained for reprinting, excerpting, copying and mirroring of the contents published on this website. Unauthorized aforementioned act shall be deemed an infringement, of which the actor shall be held accountable under the law.)