Shiliuyun-Xinjiang Daily (Reporter Zhao Mei) news: Over 2,000 years ago, Zhang Qian, a royal emissary, left Chang'an (nowadays’ Xi’an), capital of the Han Dynasty. He traveled westward on a mission of peace and opened an overland route linking the East and the West, a daring undertaking which came to be known as Zhang Qian's journey to the Western Regions. The Silk Road, stretching for thousands of miles, became an important channel for exchanges and mutual learning between Eastern and Western civilizations. Xinjiang is an important part of the Silk Road, serving as a crucial hub for trade and friendly exchanges between the east and the west. The exchange of businesses, as well as the blending of cultures, have left profound imprints here. This year marks the tenth anniversary of the Belt and Road Initiative. Let us follow the unearthed cultural relics from various regions in northwest China’s Xinjiang, revisiting the changes that have taken place along the Silk Road over time.

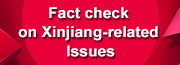

Photo shows Sihefu Seal unearthed at the Niya site in northwest China's Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region. (File photo from Museum of Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region)

During the Han Dynasty, the Tuntian system played a crucial role in unifying the western regions of China. After the western regions were unified by the Western Han Dynasty, the scale of the Tuntian system further expanded. The discovery of the official seal from Sihefu (an official department in the Han Dynasty) at the Niya site in 1959 confirms the historical fact that the Eastern Han Dynasty government reclaimed wastelands and set up specialized institutions to manage them in the Niya area. This seal, measuring only 2 centimeters in length and 1.6 centimeters in height, has the four Chinese characters "Si He Fu Yin (司禾府印)" engraved on the bottom. It was likely used by the Han government to manage agriculture. The Tuntian system during the Han Dynasty achieved multiple goals: it provided grain and forage for the army, ensured the army's combat effectiveness, spread advanced production technologies from the Central Plains, and promoted economic development and progress in the border regions.

Photo shows the "Wang Si Hai Gui Fu Shou Wei Guo Qing" Brocade unearthed in the Loulan Ancient City Ruins in northwest China's Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region. (Photo provided by Xinjiang Institute of Cultural Relics and Archaeology)

During the Qin and Han Dynasties, China's silk production and trade entered a mature and prosperous stage, and a large number of silk fabrics from the Central Plains were found in Xinjiang. Most of them were unearthed in Niya site and Loulan Ancient City Ruins. The "Wang Si Hai Gui Fu Shou Wei Guo Qing" Brocade unearthed in Gutai cemetery in Loulan Ancient City Ruins has a residual length of 22.8 centimeters and a width of 34.3 centimeters. On it, the cloud pattern is elegant and smart, and the image of the beast is vivid. The inscription "Wang Si Hai Gui Fu Shou Wei Guo Qing" is interspersed in the decorative pattern. This kind of cultural relic with the words "Guo Qing" is very rare and precious in China. Silk fabrics in Han Dynasty were added cloud patterns, animal patterns, flower patterns, and auspicious characters. On the silk fabrics, the patterns are rich and varied, and the words woven on them were particularly selected. And the brocades with auspicious language mostly came from orders or rewards from the imperial court. These brocades not only show the recognition of Chinese culture in Xinjiang, but also a referencence to the economic and cultural exchanges between the Central Plains and the western regions in China.

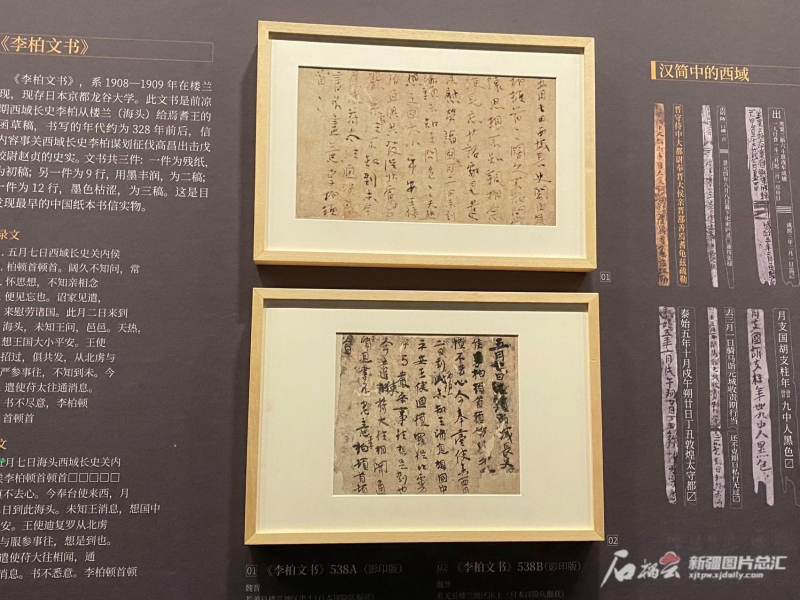

Photo shows reproductions of Li Bai's Documents displayed at the Museum of the Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region. (Photo by Shiliuyun-Xinjiang Daily/ Zhao Mei)

Li Bai’s documents were unearthed in the Loulan Ancient City Ruins in northwest China's Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region, and were obtained by the Japanese Tachibana Zuicho in the Loulan Ancient City Ruins in 1908. Currently, there are two relatively well-preserved pieces stored in the library of RyuKoku University in Japan. The ones displayed in various museums in Xinjiang are photocopies and pictures of Li Bai’s documents. In 327 AD, Li Bai served as the governor of the former Liang Dynasty in the western regions, during the same period as Zhao Zhen, a garrison commander stationed in Gaochang, betrayed the former Liang Dynasty and intended to establish his own power. After learning about this situation, Li Bai immediately reported it to the former Liang Dynasty's King Zhang Jun and requested to attack Zhao Zhen. Li Bai’s documents are draft letters written by Li Bai to the King of Yanqi, Long Xi, before attacking Zhao Zhen. They are the earliest discovered physical specimen of paper letter in China and the only historical book found in the Loulan Ancient City Ruins that records a person. They provide extremely valuable information for understanding how the former Liang Dynasty managed the western regions and for understanding this significant historical event.

Photo shows the “Tomb Owner's Life Picture” displayed in the Xinjiang Museum in northwest China's Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region. (Photo by Shiliuyun-Xinjiang Daily/ Zhao Mei)

The Tomb Owner's Life Picture is the earliest paper painting in China, unearthed in 1964 in the Astana ancient cemetery in Turpan. It dates back to the Eastern Jin Dynasty, with a total length of 106 centimeters and a width of 46 centimeters, consisting of 6 paintings, which can be regarded as ancient comic strips. The scenes depicted in the painting, such as orderly fields, flourishing crops, and advanced farming tools, are consistent with those in the Central Plains. The cultural elements depicted in the painting, such as the sun, moon, stars, toads, golden crows, phoenixes, and phoenix trees, also reflect the influence of funerary customs from the Central Plains on the western regions. During the period of the Jin Dynasty, there were constant wars, and some people from the Central Plains moved to places like Hexi to avoid the conflicts. The burial customs of the Central Plains were also brought here, and the tomb paintings of this period not only continued the style of the late Eastern Han Dynasty but also highlighted the characteristics of this era.

Photo shows the paper documents titled “Fodder Documents of Transportation Official in Jiaohe Prefecture in the 13th and 14th Years of Tianbao Period in the Tang Dynasty” displayed on the third floor of the Museum of Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region. (Photo by Shiliuyun-Xinjiang Daily/ Zhao Mei)

The paper documents titled “Fodder Documents of Transportation Official in Jiaohe Prefecture in the 13th and 14th Years of Tianbao Period in the Tang Dynasty” were unearthed from Tomb No. 506 of Astana ancient cemetery in Turpan, and are currently the largest volume of unearthed documents in Xinjiang. The document scroll is 180 pages long and is divided into 22 pieces. Mostly about the Tang Dynasty government providing horses and long-distance transportation for the military and officials in Xinjiang from 754 to 755 AD. Through this scroll of documents, people can understand that during the Tang Dynasty, there was already an official long-distance transportation institution in the Turpan area. Officials, messengers, and merchants traveling long distances not only had relay horses from Changxingfang (a specialized transportation organization), but also could eat, stay, and rest at inns along the way when they were tired and lacked horses. Two fragments in the document scroll also recorded the employment situation of the famous Tang poet Cen Shen in the local area, confirming the historical fact that Cen Shen had served as an assistant to the chief local official in the Protectorate General to Pacify Beiting.

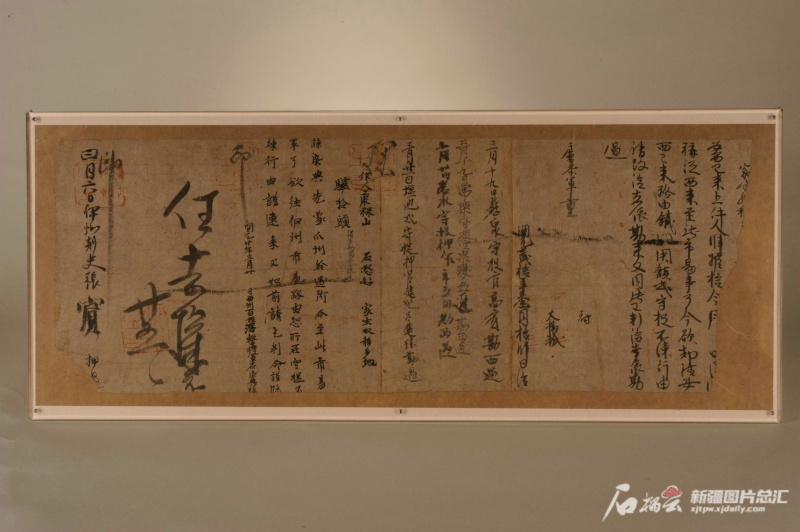

Photo shows the document "Shi Randian’s Pass" displayed in the Xinjiang Museum in northwest China's Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region. (Photo by Shiliuyun-Xinjiang Daily/ Zhao Mei)

The document "Shi Randian’s Pass" was unearthed in the Astana ancient cemetery in Turpan, dating back to the 20th year of the Kaiyuan period of the Tang Dynasty (732 AD). It is currently one of the relatively complete Tang Dynasty’s pass documents preserved in China. The document is 78 centimeters long and 28.5 centimeters wide, with 24 lines of text. There are five red seals on the document, with the first seal being the seal of the Governor's Office of Guazhou, and the three middle seals being the seals of Shazhou. The last seal is the seal of Yizhou. The document records the journey of three individuals, Shi Randian and his servants, from Anxi to Guazhou for business purposes. According to the content of the record, after successfully obtaining the pass document, Shi Randian first carried the document issued by the Protectorate General to Pacify the West to Guazhou for trading. After completing the business transactions, he requested the Governor's Office of Guazhou to issue a return pass document for his journey back to Anxi. Along the way, he also passed through Tiemenguan. The document not only showcases the prosperity of transportation and commercial trade along the Silk Road during the Tang Dynasty, but also reflects the effective implementation of Tang Dynasty policies and decrees along the route.

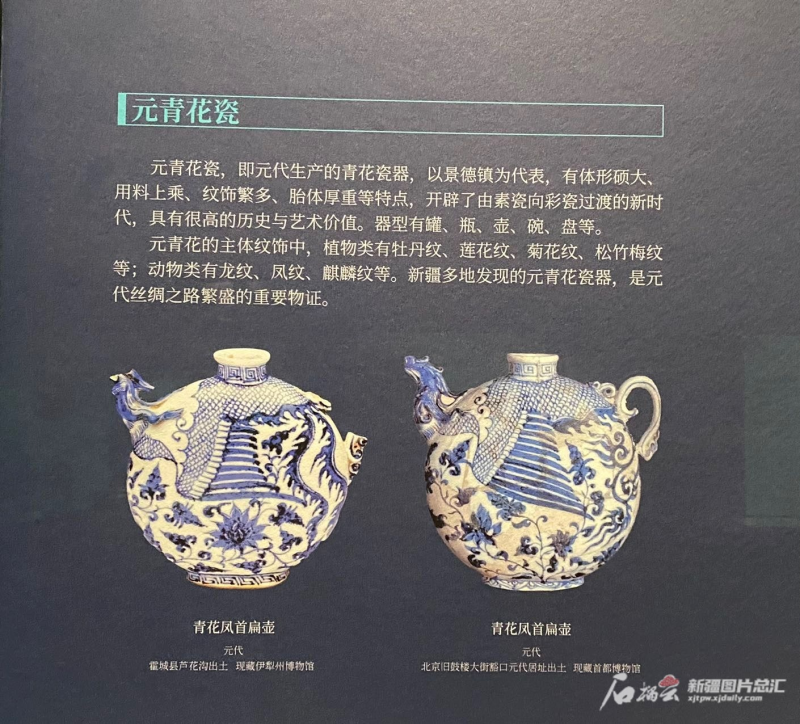

Photo shows a picture about Yuan Dynasty blue-and-white flattened pots displayed in the Xinjiang Museum (the left one unearthed in Xinjiang, the right one unearthed in Beijing) in northwest China's Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region. (Photo by Shiliuyun-Xinjiang Daily/ Zhao Mei)

The Yuan Dynasty blue-and-white flattened pot is a masterpiece of Yuan Dynasty blue-and-white porcelain, unearthed near the ancient city of Alimali in Ili Kazak Autonomous Prefecture, northwest China's Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region. The pot features a phoenix head-shaped spout with a curling phoenix-tail handle, with the body, including its wings, beautifully depicted in underglaze blue paint. The phoenix shape is painted on the upper part of the pot, while blooming peonies adorn the lower part. The shape of the pot inherits the characteristics of the Tianji pot from Central China, while incorporating the design elements of the stirrup pot used by nomadic peoples in northern China. This pot has two water outlets, so it remains to be determined whether it was a daily utensil or a wine vessel. Yuan Dynasty blue-and-white porcelain is highly valuable both artistically and historically, with only a few hundred pieces currently held in Chinese collections. Researchers believe that this piece may have arrived in Xinjiang through the Silk Road or been gifted by imperial families during the Yuan Dynasty, based on its excavation location. This artifact not only showcases the glorious history of Yuan Dynasty blue-and-white porcelain, the flourishing period of foreign exchanges, and cultural exchanges and integration between different civilizations during the Yuan Dynasty, but also bears witness to the historical connection between the central government of the Yuan Dynasty and the western regions. Cultural relics serve as witnesses and record keepers of the Silk Road, through which we can observe that the mutual learning and exchange of civilizations along the Silk Road has never ceased for thousands of years. Today, as we jointly persue the Belt and Road Initiative, let us continue to move forward hand in hand and write new chapters in the splendid history of the Silk Road.

(A written permission shall be obtained for reprinting, excerpting, copying and mirroring of the contents published on this website. Unauthorized aforementioned act shall be deemed an infringement, of which the actor shall be held accountable under the law.)