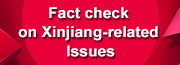

Photo shows Tai Xinlong (R) and a colleague working in northwest China’s Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region. (Photo by Gao Xin)

“Where the railway is built, personnel should be allocated”

In the distance, the sound of a train's whistle echoes.

"The train is arriving, hurry up!"

Team leader Tai Xinlong of the Hami-Lop Nur railway and his partners walked towards the platform. Several people stood in front of the train door.

"Wu, what are we having for food today?"

"Mutton, eggs, and a bag of tomatoes."

"Great!"

Beside the train door, several young fellows grinned with simple smiles.

Tai works at Luozhong Station, the last stop on the Hami-Lop Nur railway, located in the heart of Lop Nur. Although electricity and water have been connected here, daily necessities such as rice, flour, grains, cooking oil and drinking water are all delivered by train from Hami City, located 400 kilometers away.

"Guys, come and move the water." With an order from train captain Wu, Tai and his partners nimbly climbed onto the train, each carrying a 15-liter barrel of mineral water.

"The water here is highly alkaline. Once boiled, it's full of white particles, making it undrinkable," said Tai. They have to make these 15 liters of mineral water to last them an entire week.

At Luozhong Station, a commuter train arrives approximately every five days, delivering various supplies.

The train stays for five hours before making the return journey. After a brief period of liveliness, Luozhong Station once again falls silent.

Aside from the sparse population, barren landscape, and limited supplies, loneliness and monotony may be the biggest challenges faced by those working and living at Luozhong Station.

There are no shops, restaurants, or cinemas here. During the day, mobile phones can still have network signals, but at night, there is almost no signal. Table tennis, chess, and a small number of books bring joy for Tai and his partners.

In 2014, the Hami-Lop Nur team of the Hami Dynamic Detection Workshop, Urumqi West Section, under the China Railway Urumqi Group Co., Ltd., was officially established, tasked with the maintenance of equipment along the Hami-Lop Nur railway. That same year, Tai, fresh out of university, arrived here.

At that time, he didn't think too much. He believed that work was work regardless of location, so he accepted the arrangement of the company. "Where the railway is built, personnel should be allocated. This job has to be done by someone," Tai said.

Now, the team consists of seven members, who rotate shifts every ten days. The oldest in the team, Ding Peng, is 51 years old this year, while the youngest, Yong Zhishuai and Du Quan, are already 31.

Photo shows a maintenance vehicle driving towards the inspection station in northwest China’s Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region. (Photo by Gao Xin)

"If a fault alarm is triggered at any monitoring station, we must respond immediately”

At 3:20 a.m., after nearly five hours of ride, Tai and two teammates arrived at the Heilongfeng dynamic equipment detection station. Here, it is 230 kilometers away from Luozhong Station.

For the night trip, there were no roads, no street lights, and no navigation. Tai drove the pickup truck towards the direction where the railway extended and made a way in the vast Gobi desert. Along the way, there were big pits followed by small pits. People's heads hit the roof of the car from time to time, causing severe pain.

After getting off the car, the wind carrying sand hit their faces and headlights, almost drowning out their voices. Over time, Tai and his teammates developed a tacit understanding. With just one gesture, they could understand each other's intentions.

At 4:10 a.m., they began their work.

Upon opening the cover of the Trace Hotbox Detection System (THDS), a thick layer of sand and dust was revealed. Tai skillfully took out a blower and a brush, meticulously cleaned the dust from the outdoor probe box, then placed the blackbody, a type of detection device, on top of the probe box to calibrate the temperature detection.

"Here, the summer temperatures are high; if the train axle temperatures exceed the standard, there's a risk of axle breakage, which could trigger a safety incident. The detection equipment must ensure accuracy," Tai explained. According to the standards, the THDS's low-temperature detection error should not exceed ±two degrees Celsius, and during high-temperature periods, it should not exceed three degrees Celsius. "But our own requirement is to control the error within one degree Celsius."

At 7 a.m., Tai and his teammates concluded their inspection mission and embarked on the return journey, finally arriving back at their base at noon.

"The journey today was relatively smooth," said Tai. "If a fault alarm is triggered at any monitoring station, we must respond immediately, regardless of the weather conditions." In Lop Nur, sandstorms can come on suddenly and last for three to four hours.

Once, they encountered an exceptionally severe sandstorm that hit them like a wall. On the wind-facing side of their off-road vehicle, the paint was almost entirely stripped off by the sand and wind. "Fortunately, there was a culvert nearby, and we all took shelter inside for over three hours." After the storm, sand was everywhere—on their clothes, in their hair, ears, and nostrils. With every step, the sand on the railway bed was knee-deep.

On another occasion, during a snowy winter night, Tai and his teammates went to deal with an emergency malfunction. The heavy snowfall made it even more difficult to discern directions in the vast Gobi desert. "We accidentally headed in the wrong direction and ended up taking many unnecessary detours," Tai recounted. "Eventually, we ran low on fuel for the vehicle and had to request rescue. We only made it out at dawn."

Photo shows team members climb over a sand dune in northwest China’s Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region. (Photo by Gao Xin)

Implement thorough maintenance

Beneath the barren surface of Lop Nur lies the world's largest single sulfate-type liquid potash deposit, accounting for thirty percent of the country's potash resources.

For a long time, more than half of China's cultivated land has been deficient in potassium, a critical nutrient for crops. Potassium salts are a scarce mineral resource in China, and farmers have been heavily reliant on imports for their potassium fertilizers, with over 85 percent coming from abroad. The discovery of the vast potash deposits in Lop Nur has been a source of great excitement for many.

Batch after batch of entrepreneurs started from scratch and made the barren land of Lop Nur home to the world's largest potassium sulfate production plant - SDIC Xinjiang Lop Nur Potash Co., Ltd. Initially, these potash fertilizers were transported via the Hami-Lop Nur Highway. But as production increased, the highway was no longer able to meet the transportation demands.

The construction of the Hami-Lop Nur Railway was thus prioritized on the agenda. Starting from the Hami South Railway Station in the north and passing through nine stations, it extends directly to the heart of Lop Nur. The total investment for the project was 2.99 billion yuan (about 417.15 million U.S. dollars), construction began in August 2010, with a planned transportation capacity of 30 million tons per year, and it was officially opened to traffic on November 29, 2012.

"Despite the harsh conditions, the company has built a factory and and is producing potash fertilizer, we need to help them transport the potash fertilizer out," said Tai.

When it first started operating, the Hami-Lop Nur Railway only had one freight train per day. Now, during peak periods, there are seven trains running daily, with an annual transportation volume of potash fertilizer reaching 1.8 million tons.

This spring, the Hami-Lop Nur Railway has been loading 40 to 60 carriages of potash fertilizer each day. The snow-white potash fertilizer is continuously being transported out of Lop Nur, allowing an increasing number of farmers to use domestically produced potash fertilizer.

"This railway stretches between stations with nothing in between—no villages and no shop, if the train breaks down, it's a big trouble," Tai said. "We must ensure that our maintenance is carried out thoroughly to provide a solid guarantee for the transportation of potash fertilizer." Every quarter, Tai would lead the team to complete a full-line inspection.

Last year, Tai carried out a total of 210 tasks, including more than 100 night tasks, and the mileage of the pickup truck was nearly 90,000 kilometers. This year, as of July 16, he has completed 134 tasks, including 51 night tasks, and the pickup truck has run another 60,000 kilometers.

The good news is that the construction of the Lop Nur to Ruoqiang Railway, linking Lop Nur to Ruoqiang County, has commenced. Upon completion, Lop Nur will no longer be the end of the line; it will be seamlessly integrated into the eastern Xinjiang railway loop.

(Source: People's Daily, Reporter Li Xinping)