Shiliuyun-Xinjiang Daily (Reporter Zhao Mei) news: In the arid and rain-scarce Turpan Basin, there lies an ancient underground water conservancy project in China - the Karez. These Karez systems are not only the lifeblood of the desert oasis but also carry the memories and emotions of countless families. The story of Tursunnayi Hujiahmat, a tour guide, and her family across three generations is a vivid portrayal of the vitality and cultural heritage of this "underground Great Wall" of water.

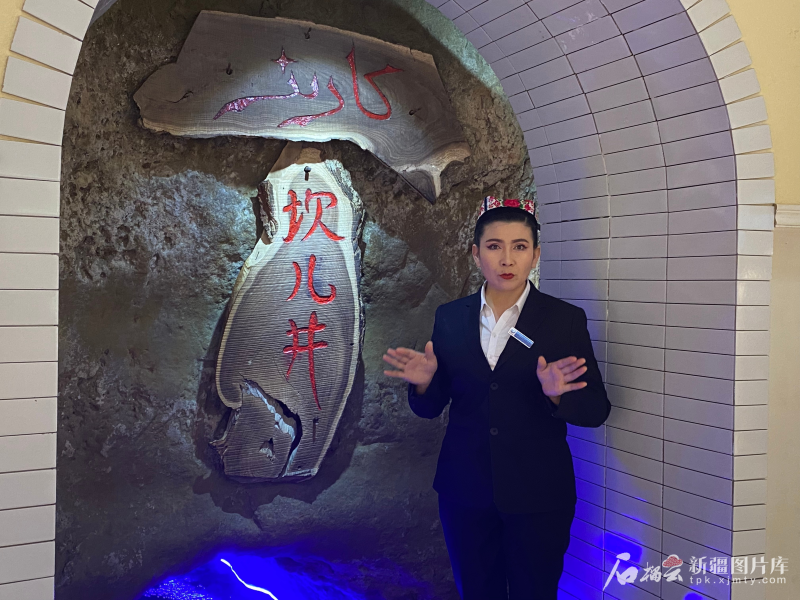

Photo shows Tursunnayi Hujiahmat gives a guide in the underground channel of the Karez in Turpan City, northwest China's Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region. (Photo by Shiliuyun-Xinjiang Daily/ Zhao Mei)

Telling the tales of the Karez to carry forward the spirit of our forefathers

"I have a special bond with the Karez because it holds unforgettable memories of three generations of my family," said Tursunnayi. She has been working as a guide at the Karez Paradise Scenic Area in Turpan City for 21 years, making her the longest-serving guide there. She is also a gold-medal guide who has received numerous accolades.

Stepping into the Karez Paradise Scenic Area, one felt as if stepping into a time tunnel. In the dim and cool underground passageways, a refreshing chill washed over you as the hidden channels snaking through the earth like an underground labyrinth. Dozens of tourists trailed closely behind Tursunnayi, hanging on her every word as she recounted the tales of the Karez. The reporter observed that beyond narrating the history and structural principles of the Karez, Tursunnayi also meticulously introduced visitors to the intricate processes of its excavation and restoration.

"How long does it take to dig a Karez?" At an underground channel display area, Tursunnayi pointed to the opening of a hidden channel and explained, "As you can see, the height of a single channel ranges from 1.5 to 1.7 meters, with a width of only 0.6 to 0.7 meters. The water temperature in the Karez stays at a chilly 15 degrees Celsius. Craftsmen had to crouch, kneel, or even lie prone in the icy, damp water to excavate, managing to dig only about two meters a day. Completing a Karez could take decades, sometimes even generations!" Tursunnayi's account clearly moved many tourists. The reporter observed some visitors marveling in awe, while others wiped away tears.

"They worked without wages and never sought any reward—this is the spirit of our forefathers who braved hardships to benefit future generations," she said. She expressed her hope that through sharing the stories of her forefathers' well-digging endeavors, more people would come to understand and appreciate the Karez.

Photo shows Tursunnayi Hujiahmat gives a guide in the underground channel of the karez in Turpan City, northwest China's Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region.(Photo by Shiliuyun-Xinjiang Daily/ Zhao Mei)

From fear to pride, the dark channel awakens the mission of inheritance

Tursunnayi's father, Hujiahmat Mijit, was a seasoned Karez craftsman. In the summer of 1987, he descended, as he often did, into a Karez more than 60 meters deep to carry out excavation and restoration work. Suddenly, the rope snapped, and he never made it back up.

"It was from that moment onward that I realized every single drop of water in the Karez was earned through the silent sacrifices of countless people," Tursunnayi said, her voice choked with emotion. That year, she was just six years old. Her mother had passed away when she was barely a year old, and with her father's death, the family's sole source of income vanished, plunging the four siblings into even greater hardship. "My younger sister was later adopted by relatives, and I was raised by my elder brother," Tursunnayi recalled. At the time, her brother was only 18, but to shoulder the family's burdens, he took on multiple jobs—growing grapes, working as a tailor, selling vegetables and clothing—to keep the family afloat.

"When I was a child, I always felt too afraid to go near the Karez. I always thought my father's shadow lingered there," Tursunnayi said. As she grew older, she enrolled in a technical secondary school, hoping to distance herself from the Karez and find a stable job elsewhere. Yet, fate had other plans, and she found herself returning to this place after all. In 2004, when the Karez scenic area was hiring tour guides, 24-year-old Tursunnayi applied for the position, and ultimately became a guide at the site.

Photo shows Tursunnayi Hujiahmat gives a guide in the museum of the Karez Paradise Scenic Area in Turpan City, northwest China's Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region.(Photo by Shiliuyun - Xinjiang Daily/ Zhao Mei)

"At first, I simply recited the script mechanically," Tursunnayi recalled. "But when I read the line, 'The Karez is a lifeline in the desert; every stretch of hidden channel embodies the craftsmen's wisdom and dedication,' tears welled up uncontrollably. In that moment, I finally understood why my father had chosen this path." From then on, she began actively researching historical records about the Karez, traveling far and wide to interview elder Karez craftsmen, listening intently to their stories of digging the channels. She resolved to honor her forebears' legacy by sharing their stories authentically. Gradually, the Karez script transformed in her heart—it ceased to be a childhood specter and instead became a cherished inheritance from her father. "After that," she said, "every time I recount the Karez's tale to visitors, my heart swells with immense pride."

Photo shows Tursunnayi Hujiahmat gives a guide in the museum of the Karez Paradise Scenic Area in Turpan City, northwest China's Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region.(Photo by Shiliuyun-Xinjiang Daily/ Zhao Mei)

The daughter's relay keeps the wisdom of the Karez flowing

Two years ago, influenced by her mother, Tursunnayi's daughter, Nurziya Wupur, became a young tour guide at the Karez Paradise Scenic Area. "My grandfather was a Karez craftsman, and the channels he dug are still flowing with water today," Nurziya Wupur said with evident pride whenever she mentioned her grandfather to visitors.

"My daughter is now in her third year of junior high, and her academic workload is heavy," Tursunnayi said. "However, during holidays and weekends, she still makes time to come to the scenic area and guide tourists.

Photo shows Nurziya Wupur, a little tour guide at the Karez Paradise Scenic Area in Turpan City, northwest China's Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region. (Photo provided by Tursunnayi Hujiahmat)

"My father dug wells to ensure future generations would have water to drink. I guide to pass on the stories of my forebears' well-digging efforts, so that more people can learn about the Karez. And my daughter is carrying this memory forward into an even brighter future," Tursunnayi added.

Photo shows Nurziya Wupur tells the story of the karez at the Karez Paradise Scenic Area in Turpan City, northwest China's Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region. (Photo provided by Tursunnayi Hujiahmat)

The Karez is a remarkable invention crafted by ancient laborers in Xinjiang to combat arid conditions and adapt to their harsh desert environment. As a living cultural heritage still in use today, it stands alongside the Great Wall and the Grand Canal as one of "China's Three Great Ancient Engineering Marvels," earning it the moniker "Underground Canal."

Photo shows visitors appreciate the Karez Paradise Scenic Area in Turpan City, northwest China's Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region.(Photo by Shiliuyun-Xinjiang Daily/ Zhao Mei)

By the time of the Third National Cultural Relics Census, a total of 1,540 Karez systems were officially recorded across the Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region, with Turpan City alone accounting for 1,108 Karez—constituting 71.95 percent of the regional total. As of July 10, 2023, Turpan's Karez inventory reveals a nuanced breakdown: 169 active channels sustain year-round groundwater flow, 21 systems are classified as "restorable", the annual runoff is 114 million cubic meters, while 939 dry channels—representing 84.7 percent of the city's total—lie dormant in the desert landscape. Carbon isotope dating analyses and cross-referenced historical archives conclusively demonstrate that these Karez systems have endured for at least 600 years, cementing their status as a living hydraulic marvel and a time capsule of desert civilization, where ancient engineering ingenuity continues to pulse beneath the sands.

(A written permission shall be obtained for reprinting, excerpting, copying and mirroring of the contents published on this website. Unauthorized aforementioned act shall be deemed an infringement, of which the actor shall be held accountable under the law.)